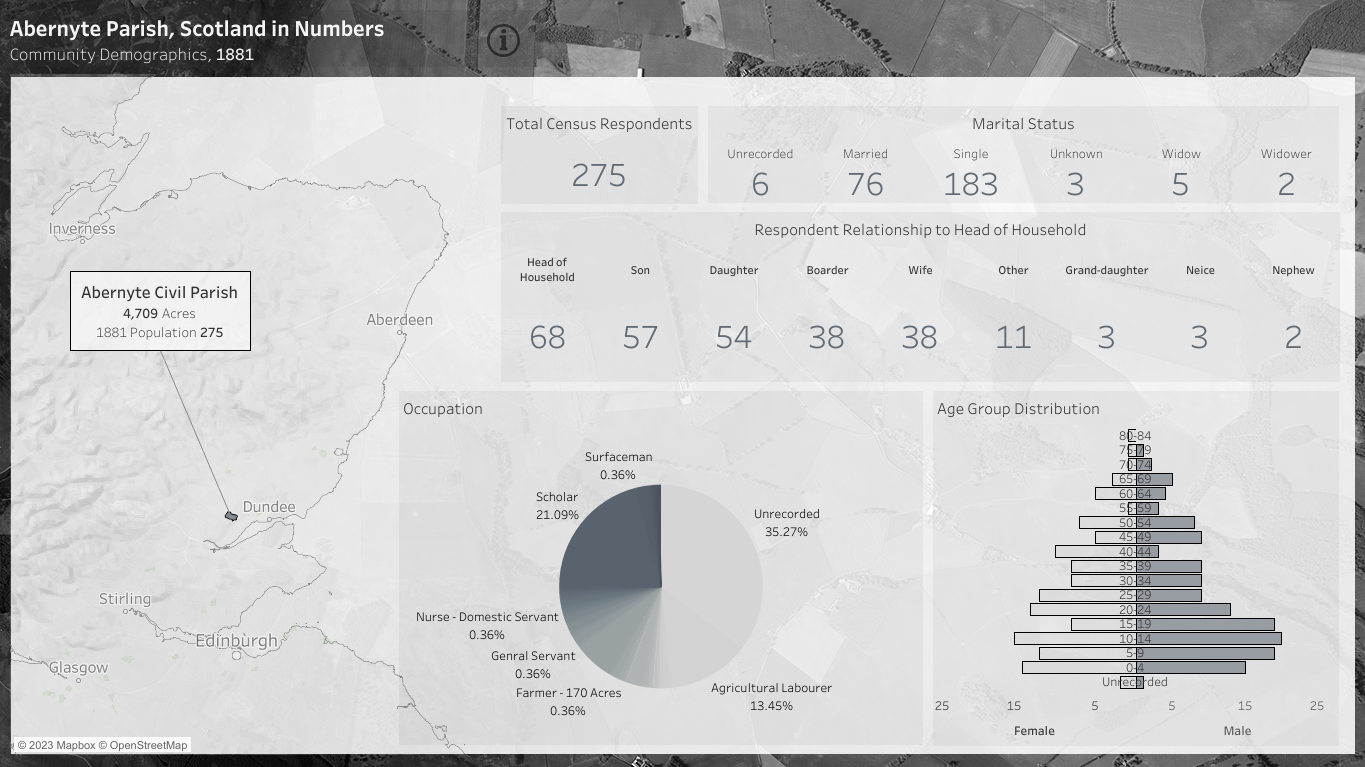

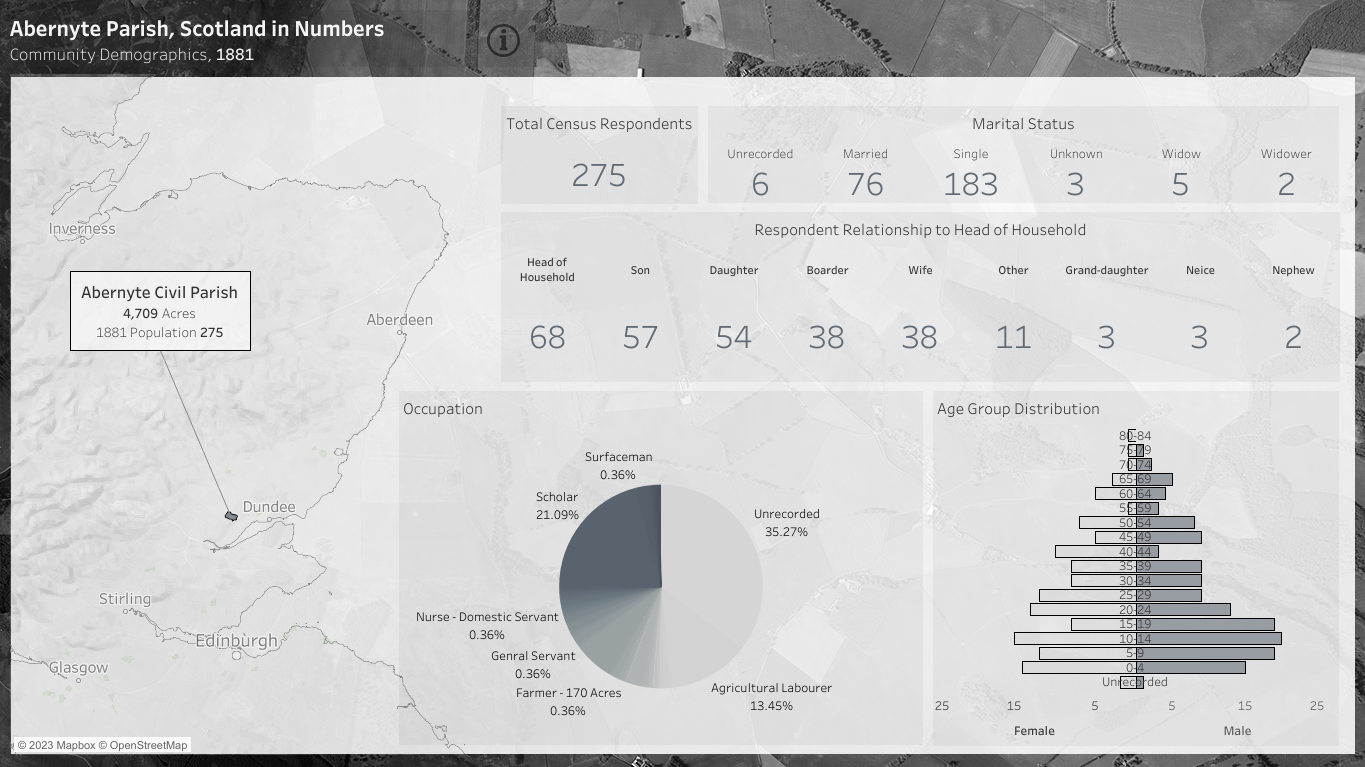

Here is a visualisation of the make up of the Parish of Abernyte at the time of the 1881 Census.

Here is a visualisation of the make up of the Parish of Abernyte at the time of the 1881 Census.

While searching for items for the Archive we came across three intriguing old photographs. The images are of a group in mostly military garb in a car in the Abernyte area.

The location is no problem, as all residents of Abernyte will recognise this as the Glen Road or B953 Abernyte to Balbeggie Road mid way between Balloleys Wood and Tulloch Ard. Of course it would not have been known by its road number until after 1922. The width of the road has varied somewhat since the photo was taken, but not by that much!

Who the group are, what they are up to and when the photograph was taken is a much greater challenge.

We can see the number plate clearly which tells us the vehicle was registered in Wimbledon in London. Careful examination of the photos also reveals an AA badge . The shape of AA badges changed greatly over the years and this badge was first used in 1911 and changed again in 1918.

Working on the not unreasonable assumption that it was quite rare to have what is obviously an expensive motor car in the Glen Road in 1911ish and that the car therefore would be quite new, I think the photo will have been taken between 1911 and 1914.

All of the occupants, bar the chap perched on the boot, seem to be in military officers uniform.

The remaining challenge:

What is the make of the car?

Who are the group?

When was the photo taken and at what event?

Firstly the car. It is a 1912 De Dion Bouton Roadster which has a V8 engine producing 35 hp from a 6.1 litre displacement.

This is an example in concourse condition at a show in America. Wow!

De Dion Bouton also made more military specification vehicles in the UK and went on to make various military vehicles during the World War I. The photographs we have show no grill name badge and a much more basic look, so this might be a military specified car.

Who are the group and what were they up to?

Here we stuck lucky with an item in the Dundee Courier from March 1913 regarding a forth coming military exercise to be held in Abernyte on the 5th April 1913! It was being organised by a 5th Black Watch Major and the detachments to take part were from the Royal Army Medical Corps under Major W.E. Foggie and the Army Service Corps under Caption C. W. Cochrane.

Also taking part, and this is the real show stopper, were aeroplanes attached to the Montrose Base who were to "locate the position of the invading or defending forces and relay the messages by flying as close as practicable to the ground and dropping them". "Motor cyclists will keep in touch to convey the messages to the commanding officers" The aeroplanes were to descend and land at Whitehills.

According to the history of the Royal Flying Corps, aircraft were first used for aerial spotting on 13th September 1914. So what we have here, in our tale, is a very early attempt in aerial spotting which easily pre-dates the official history. The Montrose Base was Britain's very first operational military airfield and was only opened in 1913 so the exercise at Abernyte must have been highly significant.

The Courier article goes on to say: " The usefulness of the aeroplane in war was amply demonstrated in the manoeuvers and the successful rush of a convoy from Dundee to a defending force at Whitehills, Abernyte pursued the "enemy" and after a hot chase had driven them into the sea"

The Courier also carried a picture of the Black Watch marching through Whitehills to engage the "enemy". This looks like it was taken on the straight between the existing steading and Den Cottage.

If you look at the rear view photograph of the original set of car photographs above, the officer on the left with the Glengarry cap is Major P. S. Nicoll ( no relation that I know of so far...I promise, it's all coincidence!) of the Black Watch. Zoom in and you can just make out a Red Hackle badge on his Glengarry. His left sleeve also has the three stripe insignia of a Major. Similarly the driver in the long right hand side view of the car has a Captain's insignia on his sleeve. The gent in cilivilian clothing perched on the rear of the car is, we believe, Mr W. J. Dickie who was the landowner of Whitehills, Pitkindie and Outfield at the time of the exercise.

Major P.S.Nicoll went on to serve in the Great War and rose to the rank of Colonel in the Black Watch. We have traced a photograph, in the Dundee City archives, of him taken while serving in Egypt in 1917.

Colonel Nicoll resigned his commission in 1921 and died in 1942. There is a further painting of him in the McManus Gallery in Dundee.

A superb wee snippet of local history all from three nearly anonymous photographs. It is slightly disturbing to recall that this was all taking place in sleepy Abernyte before the conflict that engulfed all of Europe at the cost of so many lives.

Another facinating glimpse in to Abernyte's past has been unearthed.

In 1875 the Gordon Steam Shipping Company commisioned a three masted sailing barque of 728 tonnes built on the Clyde at Dumbarton by McKellar, McMillan and Company.

The ship was called Abernyte

Another item to add to what we know of the SS Abernyte comes from no less a publication than the Shetland Times of 1880. On Saturday 21st February it carried an advertisement for the imminent sailing of the SS Abernyte from the Clyde bound for New Zealand.

It was also captured in oils in full sail.

It traded as a general cargo vessel until it was wrecked in fog off Lizard Point in 1898 carrying a cargo of Nitrate of Soda.

The Board of Trade enquiry found:

"On 29th December, 1897, the "Abernyte" left Caleta Buena, Chili, with a cargo of about 1,150 tons of nitrate of soda bound for Falmouth for orders. The freight payable for this cargo was stated to be £1,800, and it was fully covered by insurance. Her mean draught of water was about 17 ft. 6 ins., and she was about 3 ins. by the stern. She had a crew of sixteen hands all told, only three of whom formed part of the original crew which had left the United Kingdom. During an intermediate voyage she had lost two boats, but when she left Caleta Buena she still had one life-boat, one jolly-boat, and a dinghy, more than sufficient to comply with the requirements of the Act in that respect. She had a complete outfit of compasses, viz., a standard compass on the mizen-mast, a steering compass before the wheel aft, a tell-tale in the skylight, and a spare one below, besides five spare cards and a boat compass. Owing to the inconvenient position of the standard compass, the vessel was navigated entirely by the steering compass. These compasses had been overhauled by Messrs. Dobbie, Son, and Hutton, of Fenchurch Street, London, in September, 1895, but there was no evidence to show when they were last adjusted, certainly not for several years. This omission, however, does not appear to have caused any practical inconvenience in the navigation of the ship beyond a certain degree of sluggishness experienced when entering the English Channel, the master stating that the deviations were moderate in amount, and that, with the exception just mentioned, he had no complaint whatever to make regarding them.

After a tedious but otherwise uneventful passage, the "Abernyte" made the Bishop Lighthouse, Scilly Islands, about 10 a.m. on the 7th May last, and a course was set and steered to pass five or six miles south of the Lizard. Between five o'clock and six o'clock p.m. the "Wolf" was sighted, and when abeam was estimated to be five or six miles distant, but no cast of the lead was taken nor other means used to verify the position of the ship; and it may here be noted that the lead was never used after the Bishop Lighthouse was made on the morning of the 7th May. She still continued on her course towards the Lizard, the weather being fine and clear, with a moderate breeze from the S.W., the ship making about three knots. The Lizard lights were made between eight and nine o'clock, and it is at this point that the master seems to have made the fatal mistake which eventually led to the loss of the ship. For three hours, or until 11.30 p.m., the lights were continually in sight and in line, which, had the master consulted his chart with ordinary intelligence, was a sufficient indication that he had not the offing he was reckoning upon, and that he had passed the "Wolf" much closer than he estimated, and that also if he continued his course he must inevitably strike on the Lizard Point. At 11.30 p.m. the weather became foggy and the lights were obscured and not again seen. The same course was continued until about 1.30 a.m. on the 8th, when it was altered one point towards the land. At midnight sail had been shortened to topsails and foresail.

Shortly after the course had been altered, the noise of the surf was heard, and directly afterwards breakers were seen on the starboard side. it being evidently impossible to stay the ship owing to the vicinity of the rocks, the master attempted to wear her, calling all hands and making sail. She appears to have reached along the shore for some little distance on the port tack, but owing to the lightness of the wind and a heavy ground swell she had got into, she gradually drifted on the rocks off Rill Head and became a total wreck. The crew, who did not save any of their effects, got into the life-boat and pulled seawards. While in the boat the crew heard the siren on the Lizard, which had not been previously heard.

About daylight they were picked up by a pilot cutter and ultimately landed at Falmouth.

No lives were lost.

The Court having carefully inquired into the circum stances attending the above-mentioned shipping casualty, finds for the reasons stated in the Annex hereto, that the casualty was caused by the master, Mr. Edwin Cardwell, neglecting to use the lead and ignoring the fact that he had brought the two lights of the Lizard in a direct line.

The Court finds the master in default, and suspends his certificate for six months."

In 2021 a group of divers lead by Mr Ben Dunstan in the Scilly Isles were able to take advantage of rare, calm conditions at the wreck site and had a series of successful dives onto the wreck. It is relatively unvisted by divers and they were able to recover many interesting artifacts from the ship including the sextant and the lead depth line which was commented on at the board of enquiry as their use had been neglected by the ships master which caused the wreck.

These images are all courtesy and copyright of Ben Dunstan©2021